The Impact of Privatisation on the Sustainability of Water Resources

This research investigates potential contributions by the privatization of water production to sustainability of water supply. The main objective is to examine the perceptions of stakeholders concerning privatization as a water governance model and its contribution to water sustainability.

This research provides a robust reference for future planning in the water sector, hinting at the importance of considering public-private partnerships at the federal level as an appropriate model for water sustainability.

Global Distribution of the World's Water

More than two and a half millennia ago, the Greek philosopher Thales of Miletus said “best of everything is water” (Biswas, 2005; p.229). Indeed, water still remains the source of life although the world has changed dramatically. Water is the most important natural resource on our planet Earth. It is the basis of life that all organisms depend on for survival. Water is present on Earth as fresh or saltwater. About 97.5% of water is saltwater with a remaining 2.5% of fresh water.

Humans can only consume freshwater; however, only about 0.5% of the Earth’s freshwater is accessible (UNFPA, 2001). Figure 1 depicts the distribution of water resources in the world. Although freshwater is a renewable resource, the world's supply of fresh water is decreasing. Water demand already exceeds supply in many parts of the world, and as world population continues to rise conditions are expected to worsen (Chenoweth, 2008). According to the State of the World Report by UNFPA (2001), the global population has tripled over the past 70 years and the water use has grown six-fold. This is the result of industrial development and increased use of irrigation. Worldwide today, 54% of the annual available fresh water is being used. If consumption per person remains steady, by 2025 we could be using 70% of this total.

Figure 1 Global water distribution

Faced by these facts, it is clear that the un-substitutable water is the resource that will define the limits of sustainable development in the near future (UNFPA, 2001). This highlights the need to manage freshwater resources and rationalize their use. To this end,

many international initiatives and agreements have been developed; most important of which are:

- United Nations Conference on Environment and Development: convened in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, affirming that: “the holistic management of freshwater as a finite and vulnerable resource, and the integration of sectoral water plans and programmes within the framework for national economic and social policy are of paramount importance for actions in the 1990s and beyond” (Earth Summit CD-ROM).

-Agenda 21, Chapter 18: concluded at Rio (1992), lists a number of Integrated Water Resources Management programme activities (Earth Summit CD-ROM).

- International Conference of Water and the Environment: convened in Dublin 1992: calls for new approaches to the assessment, development and management of

freshwater resources (UNEP 1991; UNEP, 1992).

These and other initiatives have raised the world’s concern about freshwater availability and the means for its sustainability. In effect, new paradigms for water management and conservation have been developing during the last 20 years to attend to the water problem (Chang & Griffin 1992). The main contributors to the increased water withdrawal are unsustainable water demand, lack of proper management (leakage, waste etc.), and the free use of water – when considered a social good. Mitigating these factors requires a holistic review of the management of water resources including control on access and use, conservation, protection from pollution and prevention of waste.

The Importance of Water

Since the dawn of history, people have valued water resources as the source and guarantee of their survival. They have travelled to areas rich with water and settled in such areas. This change from nomad to settler was accompanied by a shift in the means of living as well as in the interaction between people and resources (Goma et al., 2001).

Subsequently, consecutive demographic, social and economic factors further impacted the interaction of people with water resources and necessitated the adoption of various methods of developing and managing these resources in adaptation to their changing environment and emerging needs. Governments and societies have, long since, treated water mostly as a free or a social good.

The increasing rivalry, nevertheless, for inadequate water supply around the world has led to differences in objectives and methods of water management. Furthermore, the forces that penetrate the society, such as globalization, urbanization and population growth, combined with the introduction of technological changes and accessibility to information made existing water management structures outdated (Figueres et al., 2003).

Scarcity and meeting water demands

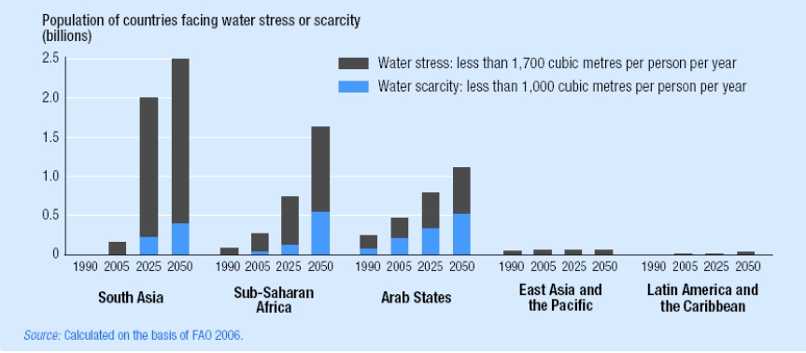

Water scarcity occurs when the demand for water exceeds the available amount of water. Water scarcity also occurs when the poor quality of water limits its usability. Therefore, water quantity is not the only benchmark indicator for scarcity, water quality also has a bearing (UNDP 2006). Usually, scarcity is assessed by analysis of the population-water equation. The norm, as such, is to consider 1,700 cubic metres per person as the national threshold for meeting water requirements. Consequently, water availability below 1,000 cubic metres represents a state of “water scarcity” and below 500 cubic metres represents “absolute scarcity” (Rijsberman, 2004). Based on this threshold, the figure below represents water scarcity states in different regions around the world.

Figure 2 Water status in different regions

Growing demand for water is the first of the components of a water scarcity situation. Population growth increases demand for water for the production of food, but also fordomestic and for industrial uses. This adds social and economical parameters to water related problems including scarcity. The three sectors compete for water allocation and this competition will get more intense in the future. In fact, population growth and rapid development comprise the major factors affecting water resources and their sustainability in the world.

As of 2008, the world's population is believed to be more than 6.7 billion (IDB). In line with population projections, this figure continues to grow at an unprecedented rate. The world's population, under the current growth trajectory, is expected to reach nearly 9 billion by the year 2042 (Worldometers; IDB) with an average growth rate of about 2.19% (Nielsen, 2006; IDB).

However, the annual renewable water resources in the world amount to about 48,619 km3 only (Gleick, 1998). As such, the high population growth rate exceeds the rate of water resource development. Consequently, the annual per capita share of water resources is decreasing, and at an ever-increasing rate. As such, the rate of development and usage of water should be maintained at a lower level than the renewable rate of water resources (EEA, 1999). Human kind should be aware that the water resources are indispensable "partners-for-life", in a partnership in which humankind should not be dominant. Therefore, humankind should realize that there is a limitation of development and usage of water resource.

However, what is usually forgotten is the policies’ role in water scarcity. This is basically apparent in terms of acts of commission and omission (UNDP 2006). For example, perverse incentives as an example of commission acts are damaging because they promote overuse. This is observed in areas where water is provided for free or subsidized, which necessarily remove the incentive to conserve water or at least rationalize its use (EWG 2005). As such, one can only imagine the case in the Middle East and North Africa, where the cost of water is set well below cost-recovery levels even though the scarcity value of water is much in evidence (Shetty, 2006; Abderrahman,

2002).

In parallel, acts of omission has a breakthrough impact on scarcity particularly that to date little if any country show the deterioration or depletion of water in the national accounts as a loss, or depreciation, in natural resource assets. As such, national accounting conventions reinforce the market blind spot for water where natural services are seldom traded in markets, have no price and thus are not properly valued (Repetto et al., 1989; Solórzano et al., 1991; Daly & Cobb, 1989).

GDP accounts for losses of watercapital are expected to change economic and environmental performance indicators for a large number of countries and will pass the message on sustainability to future generations (Repetto et al., 1989; Solórzano et al., 1991; Daly & Cobb, 1989).In this regard, the World Bank, in an attempt to comprehensively understand and present the issue of water scarcity, has identified different factors that interplay to cause water scarcity, an important part of which comes from outside the water sector (IBRD/WB,2007).

Hence, the World Bank stresses the role of institutions and policies in the development of water problems and scarcity because, as they explain, it is the institutions and the policies that define how well countries manage their resources, including water resources (IBRD/WB, 2007). For example, the WB has identified three types of scarcitiesn the MENA countries, including UAE that defines and limits water management in these countries and consequently contributes to their water scarcity. These types consist of (a) scarcity of the physical resource; (b) scarcity of organizational capacities; and (c) scarcity of accountability for achieving sustainable outcomes (Refer to Section 2.5 below for the detailed analysis of water scarcity in MENA countries) (IBRD/WB, 2007). This perspective stresses the social and economical parameters of water scarcity, thus increasing the complexity of the notion.

After all, these represent important reasons for why many countries face critical difficulties in ensuring self-reliance in meeting their water demand (Comair, 2005; Al- Alawi, 1998). This issue is further heightened when the link between water and food security is raised. For instance, currently, agriculture uses up the biggest part of the total water use and it seems probable that availability of water rather than land will be in the future the binding constraint to expanding food production worldwide.

It becomes clear, here, that there is no obvious solution for water scarcity as it is multifaceted and branched. However, there is indeed one solution that serves all which is sustainability i.e. sustainable development and sustainable natural resources use.. This introduces the issue of sustainability of water resources’ particularly in the developmentand usage of water resources. As such, the following section will introduce watersustainability and highlight the practices (planning, management, monitoring…) that guarantee the environmental conditions, which is needed to ensure water resources being renewable.

Sustainable Development and Water Sustainability

The concept of "sustainable development" dates back to the famous publication Our Common Future. Back then, sustainable development was defined as: "to ensure meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs" (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987). This points that sustainable development does imply limitations imposed by technological and social impacts on environmental resources and by the carrying capacity and resilience of natural systems to absorb human activities.

Therefore, sustainable development clearly indicates that the carrying capacity of environment is limited. Applying the sustainable development concept in the water resources realm, it is development and utilization that meet current water needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs -- both for water supplies and for a healthy aquatic environment. The notion of sustainable development consists of three dimensions: the social, ecological, and economic dimension (Rogers et al., 1998; WSSD 2002; Hildering, 2004).

Criteria have further been proposed to make these three dimensions more tangible (Daly, 1996; Rogers et al., 2002). These criteria are ecological sustainability, social equity and economic efficiency.

1. Social equity: is measured by the Gini-coefficient, which measures inequality of a distribution of resources. The Gini-coefficient is a ratio with values between 0 (uniform distribution) and 1 (fully inequitable distribution) (Verkerk et al., 2008).

2. Ecological sustainability: is measured by the ‘criticality ratio’, a withdrawal-toavailability ratio. As such, ecological sustainability occurs when the criticality ratio remains below 0 and a ratio above 0.4 represents water scarcity (Raskin etal., 1997).

3. Economic efficiency: is measured by ‘the criterion of Pareto efficiency, which defines the economically optimal situation as the state in which no individual can be made better off without another being made worse off’ (Verkerk et al., 2008).

Moreover, when the definition of sustainable development is converted into economic terms, it can be understood as “the development that pays its full cost during the process of development” (Panayotou, 1994). In other terms, it is development that accounts for all costs from production to disposal including: cost of resources’ depletion called a user cost, cost of environmental damage called environmental cost … etc. and it receives no subsidies except in proportion to positive externalities that it generates (Panayotou, 1994).

According to Panayotou, this development is “internalizing the conservation of resources, the protection of the environment and the provision of environmental and social infrastructure to the very economic activities and actions that place additional demands on these resources" (Panayotou, 1994). On the other hand, from the perspective of water sustainability, it should transcend beyond quantity and quality. It should assess water reuseand water resources management systems, in terms of their broader environmental and social impacts (Hermanowicz, 2005).

However, there is a lack of a framework for assessment of water sustainability in its broader sense. Current definitions do not offer proper aid to an engineer, a decision maker or an accountant, for instance, to deal and apply sustainability. As such, if sustainability is to be incorporated in business activities, it is argued that it must have a reasonably simple and quantitative definition. This could be through pricing which will, for instance, at least allow the comparison of alternatives.

To better explain achievement of water sustainability, at the Johannesburg World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) in 2002, the Technical Advisory Committee of the Global Water Partnership introduced the concept of Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM), to promote sustainability of water resources and defined it “as a process, which promotes the coordinated development and management of water, land and related resources in order to maximize the resultant economic and social welfare in an equitable manner without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems,” and emphasized that water should be managed under the principles of good governance and public participation.

Historically, water management has been institutionalized in an integrated way over centuries. In the 1940s, an early version of IWRM occurred when the Tennessee Valley Authority began to develop the water resourcesfor that region (Barkin & King, 1986; Tortajada, 2004; Embid, 2003). Later in 1977, at the United Nations Conference on Water in the Mar del Plata, IWRM was also the recommended approach to incorporate the multiple competing uses of water resources. The above overview of the concept of water sustainability and the criteria explicitly showed the indispensable need for strong and good water governance to accompany and ensure water sustainability.

According to the World Water Assessment Programme (2003), the weaknesses in governance systems, is what greatly impeded progress towards sustainable development and the balancing of socio-economic needs with ecological sustainability. They even go further to note that the water crisis is essentially a crisis of governance (WWAP 2003). After all, the core challenge with water governance is to realign water use with demand at levels that maintain the integrity of the environment (UNDP 2006) i.e. achieve a condition of social equity, ecological sustainability and economic efficiency indirectly assuring sustainability.

Water Governance

Governance models are descriptions of the ownership and organizational structure, and allocation of responsibilities and risks for operational management and/or infrastructure maintenance and improvement of a business/industry (Bakker, 2003).

Governance models are also interchangeably called business models. As such different business or governance models allocate ownership to different stakeholders. Governance models usually describe a set of structures, functions and practices that define who does what, and how they do it (Bakker, 2003). In the case of water supply, two main governance models apply. One of which is the allocation of ownership of assets and management of assets to the government.

The other is their allocation to the private sector. Emerging also is the model in which public and private actors partner for the management of water sector. Water governance in general comprises a range of political, organizational and administrative processes through which (Bakker, 2003; Rogers & Hall 2003):

1. Communities articulate their interests,

2. Decisions are made and implemented,

3. Decision makers are held accountable in the development and management of water resources, and

4. Delivery of water services is overseen.

It is important to note that the United Nations General Assembly in 2003 proclaimed the years 2005 to 2015 as the International Decade for Action 'Water for Life' (UN-Water, 2003, 2006; Martinez Austia P. and Van Hofwegen P. 2006; Verkerk M.P. et al. 2008).

In this sense, as a commitment, achieving good water governance is perceived as a global challenge; however, usually water governance is generally seen as a local or regional issue (UNGA, 1997; Verkerk M.P. et al. 2008). As such, the international water community has not recognized the necessity of global coordination in ‘water governance’. As a result, most efforts focus on seeking proper institutional arrangements (structures or mechanisms of social order and cooperation) at a local basin level.

Water governance at the local level derives from the ‘the way people use and maintain water resources’ (Verkerk et al., 2008). This is supported by the subsidiary principle, which states that water issues should be handled at the lowest governance level possible and by the fact that water resources in the global sense are not scarce. It is understood that ‘aggregate annual withdrawals are below annual renewable water resources at the global level’ (Verkerk et al., 2008; Gleick, 1993; Postel et al., 1996; Shiklomanov, 2000; Vörösmarty et al., 2000; Zehnder et al., 2003). The actual issue is then the water demand and supply disparities at local scales.

Further to this discussion, Hoekstra (2006) clarifies how water governance has a global dimension. He relates this to the multiple global factors [information] climate change, (ii) privatization of drinking water, sanitation and irrigation services, and (iii) increasing ‘virtual water trade’ between nations which are directly or indirectly affecting water resources. However, according to Verkerk et al. (2008) institutional responses have not kept pace with the effects of climate change, privatization and trade liberalization that have led to or are expected to lead to changes in water supply or demand in various places.

However later, this was reflected after World War II and the expansion of the era of globalization, commoditization and neo-liberalism, where privatization gained increased enthusiasm in the water sector. Initially, governments have been the main provider of water, electricity, waste collection, and health services based on the raison d'être of governments, which places the delivery of services to a country’s citizens at its core. As such, the known paradigm of water management puts the public sector at its centre as most countries depended in the past on the public sector to provide water services to the population.

Nevertheless this was not free of problems and complaints, which resulted from disputed efficiency and quality of water supply and reliability services. Even in developed countries public systems perform with lower competency than private systems (Easter, 1993; Estache & Rossi, 1999). In fact, it has been reported that government operation and delivery of water services has been subject to multiple problems that have caused undesirable results to both the government and the customer (Comair, 2005). It is believed that most government operated water production, distribution and collectionmsystems are characterized by inefficiency and ineffectiveness.

Reasons reside in the weakness of the institutional framework or the poor operation and maintenance and the lack of monitoring allowing illegal connections and thefts (Nyangeri Nyanchaga, 2003), as well as in the ineffective pricing (Nyangeri Nyanchaga, 2003; Dawoud et al., 2007). Naturally, this leads to poor service delivery, low revenues, poor operation and maintenance, high unaccounted-for water loss, low capital investments, low accountability of water undertakers, inadequate incentive system resulting from absence of transparency in financial management, overstaffing and wrong deployment of staff, and unsustainable operations and lack of regulation and enforcement (Nyangeri Nyanchaga, 2003; Azpiazu et al., 2003; Mashauri, 2003; Torregrosa, 2003).

Hence, a number of institutional arrangements (i.e. water markets) and other institutional forms for increasing efficiency and improving water supply and reliability services were being sought for water management (Easter & Hearne, 1994). The world today however is witnessing a restructuring of this governance model and mainly a shift from public management to privatization in water production and services (Comair, 2005).

This has expanded particularly due to the growing literature on water markets that documents the capacity of markets to create efficiency gains and to provide an efficient system for allocating water among sectors (Easter & Hearne, 1994; Chang & Griffin, 1992; Colby, 1990; Crane, 1994). As such, published literature presents multiple examples of successful water privatization in different parts of the world, including the Gulf countries, Latin American, as well as some European countries.

Basically, there are three main reasons for restructuring which include improving performance, sourcing finance, and meeting new legislative requirements (Bakker, 2003).It is insightful to note that almost all countries expressed the same reasons for water privatization (Al Alawi, 1998; Azpiazu et al., 2003; Mashauri, 2003; Nyangeri Nyanchaga, 2003; Darwish et al., 2007, Darwish & Al Najem, 2005). These reasons, fitting in the above categorization, mainly included:

- Poor water quality poor water administration,

- Service inefficiency and ineffectiveness,

- The inability to expand the service, and

- The need to remove the financial burden from governments’ budgets.

In summary, countries are observed to be adopting water privatization in an attempt to improve the quality of the water services supply, to expand the water services, to improve efficiency in operations and proper maintenance and to secure financial resources for investment (Mashauri, 2003), as well as to incorporate new technologies (Azpiazu et al., 2003). As such, privatization is observed as a tool to reduce the burden on public budgets while improving the customer service (Comair, 2005).

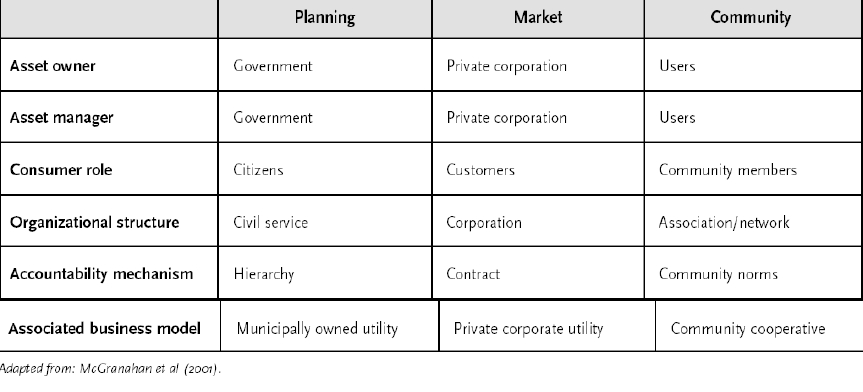

This mentioned, it is important to clarify that today there exists a wide range of business models and governance structures for water management systems in the world. They range from full public models to full private models and mainly include 1) government management, 2) community cooperatives, 3) corporatized utilities, 4) government delegated management and 5) privatization also called direct private management or divestiture (Bakker, 2003).

The table below summarizes the most important differences between these three models: the planning, the market and the community models.

Table 3 The three governance models

For instance, the difference is apparent between the planning and market governance models where the owner and operator of assets is the government and the private corporation respectively. It is important to note that under the planning model, the consumer is a citizen while s/he becomes a customer under the market model.

Another important difference is that the hierarchy in the planning model serve as the accountability mechanism, while the contract serve this purpose under the market model. On the other hand, it is to be noted that practical implementations of these models revealed the emergence of hybrid models. These are apparent in, for example, the delegated management contracts and corporatized utilities which adopt elements from both the planning and market models (Bakker, 2003).

Most representative examples from the world include the cases in France and England. In France, private-sector management via management contracts is widespread. But water supplies infrastructures are owned by the municipalities who are forbidden to sell their infrastructure and do retain control over long-term strategic planning, which is characterized by features of the planning approach (Bakker, 2003). In England on the other hand, the water supply and wastewater industry have been fully privatized since 1989, where the market model has been chosen.

However, England has created extensive regulatory frameworks and regulatory agencies for the water sector, to protect consumers and public health (Bakker, 2003). Resuming, a shift from public management to privatization is indeed a change in governance, a shift from a governance model to another. Introducing this governance model i.e. privatization entails a paradigm shift in approaching, managing and analyzing the processes involved. It entails both organizational and institutional changes. It is indeed not easy and risky, as there exists no one model that suits all. However, it is important to remember that there is an ongoing debate on water privatization, the concept and the essence.

Basically, it is a debate on the commodification of water that stems from different approaches and perspectives to define, view and manage water. It is the same debate that rises on the management of any common resource in parallel to the known ‘tragedy of the commons’. As such, no one can address water, sustainability and privatization without dwelling on this debate.

Water: a human right or a human good

The major debate on water issues lies on the perception of water as a right or good. It is the ongoing struggle between viewing water as an economic commodity whose use and distribution is determined by profit or as a fundamental human right (Barlow & Myers, 2002). Therefore, it is a simple dichotomy between economic efficiency and basic welfare or human rights (Pradhan & Dick, 2003).

This debate heightened after the 1992 Dublin Water Conference and World Water Vision described water as an economic good. However, the aim of this statement was to promote that water be priced at a level that makes people use it sparingly (Faruqui, 2003). The argument behind this is that charging for water will conserve it. But still, the idea that water is an economic good remains controversial. In this regard, there are two main opposing arguments, one that recommends that ‘the state’ control natural resources to prevent their destruction while another that recommends privatization as the solution for the problem (Ostrum, 1991).

The human right to water is generally derived from the human rights to life, including food, drinking water, health, and a clean environment (McCaffrey, 1997). The human right to drinking water also stems from the human right to life: without drinking water people die (Beckmann & Beckmann, 2003).

Believers and supporters of the view of water as a human right challenge the view of privatization or the consideration of water as an economic good. They argue that commodification of water is ethically, environmentally and socially wrong because it bases decisions of water allocation on

commercial, not environmental or social justice considerations (Barlow & Clarke, 2002).

Proponents of this view point further refuses privatization because it entails principles of scarcity and profit maximization rather than long-term sustainability in water management. They claim that some transnational corporations, backed by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, are increasingly forcing Third World countries to abandon their public water delivery systems and contract with their companies through what is called structural adjustments (Barlow & Clarke, 2002; Verghese, 2003).

They support their arguments by the fact that these transnational companies and corporations bring in about $200 billion a year –from an $ 800 billion worth global water market- from ownership or operations of water systems across the globe while only serving 7 percent of the world’s population (Barlow & Myers, 2002). On the other hand, privatization of the water sector is mainly promoted by “neo- liberal” economists.

Proponents of commodification of water base their argument on the perceived widespread corruption of the public sector in many developing countries (Segerfeldt, 2005). Defendants believe that unless water is treated as an increasingly precious commodity and priced to reflect its value much of it will be wasted (Barlow & Myers, 2002). In support of their argument, they highlight the cases of water scarcity, water related fights, appropriation as well as wasteful use of water resources, lack of finances for the effective management of water resources and attribute them to public management of water resources. In this sense, they promote public management as a recipe for over- consumption (Segerfeldt, 2005) and offer privatization as the only best solution (Verghese, 2003).

Islam, Christianity, Judaism and other religions call for water as a human right. Furthermore, in Islam, which is most important within the context of this study, water is a social good owned by the community (Faruqui, 2003). By further elaboration of the Islamic emphasis on equity, water is considered a fundamental human right (Faruqui, 2003).

According to Islam, a government may fully recover its costs for providing water to its people, but at the same time it must provide a social safety net to protect the poor (Sabeq, 1981; Zouhaili, 1992; Faruqui, 2003). This does not preclude the opportunity for privatization within the water sector because a government following the principle of maslaha or public interest, could ‘privatize’ an existing public utility, or give a private corporation the right to provide water services and recover costs (Faruqui, 2003). The model must be one of a public – private partnership, where the government maintains its ‘ownership’ of water for the community (Faruqui, 2003).

Water is known to be a common good. Hence, the arguments presented are mainly about how to manage this common good. However, as observations in the world showed that neither ‘the state’ nor ‘the market’ is uniformly successful in enabling individuals to maintain sustainability in water use (Ostrum, 1991); therefore this debate should be guided more towards finding ‘an ethical balance’ among using and preserving our water and land resources. While sustainable development aims to achieve a balance between the utilitarian use of and respect for the intrinsic value of Earth’s resources; then,mwhatever management, that can ensuresustainability is worth adopting.

For the purpose of this study, the following sections attempts to explore the shift emerging in the water sector towards privatization, the reasons behind it and its impacts on the market, the clients, and the product. It will also include literature review of the impact of privatization of water resources in different countries around the world in their pursuit of water resources protection.

Privatization, a Water Governance Model

Water privatization started in most developing countries in parallel to water reforms in the 1980s (Castro, 2007). Privatization of water is becoming very popular in different parts of the world particularly in Latin American countries (Castro, 2007).

Privatization levels and modes in the water sector differ among countries as different public-private partnerships exist. While most privatization is limited to the distribution and maintenance works, there exist cases of full privatization, including ownership of assets (Comair, 2005). In view of this increasing trend, the debate on the impact of privatization on the water sector, on the country and on the resources is gaining more significance and is still unsettled.

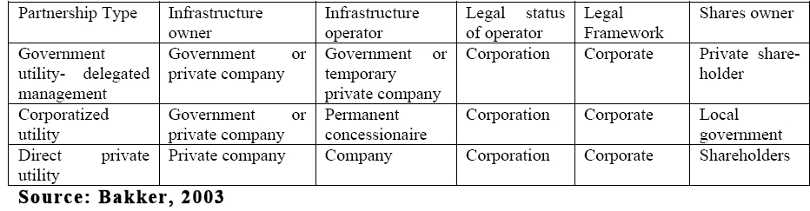

Published academic literature shows that privatization has been adapted to varying levels among the different countries. These levels stem from the different possible publicprivate partnership combinations, where each has its specific allocation of rights, duties and gains. A public-private partnership arrangement is, by definition, a contract between a public client and a private service provider (WB, 2007).

It is important to note that the first public-private partnership (PPP) contracts in the water sector derived mainly from the French historical model of public service delegation (gestion déléguée). At present, PPP provides water to 5 percent of the world’s population, and private financing in water supply and sanitation accounts for somewhat less than 10 percent of the sector’s total investment.

Table 4 summarizes the potential forms of public – private partnerships in the water sector

As Table 4 shows, basic differences exist among these partnership types, which in turn result in different impacts on the privatized sector. ‘A corporatized utility is a public owned corporation that operates like a private business, with the government acting as the shareholder’ (Bakker, 2003). It is not subject to the public law.

‘Corporatization is often a precursor to full privatization, and is sometimes recommended as an intermediate step prior to privatization’ (Bakker, 2003). However corporatization does not imply full privatization. With respect to delegated management, water utility management is contracted out to another entity i.e. ‘outsourcing of core activities such as construction, operations and maintenance, and customer services’ (Bakker, 2003).

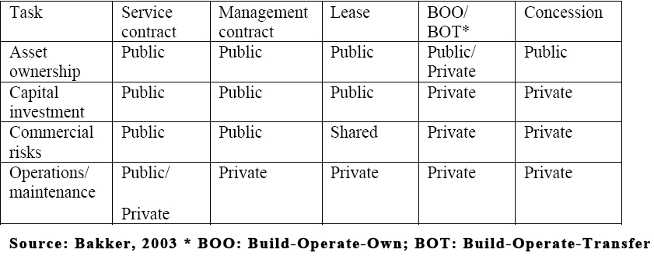

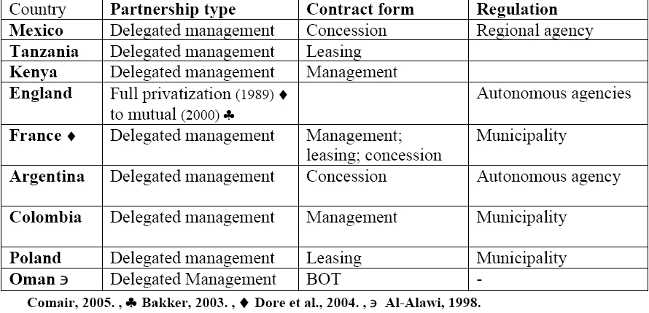

This model is also referred to as “private sector participation”. Under delegated utility, different contract forms may be signed. Table 5 summarizes the different forms of contract and allotments under delegated management.

Table 5 Contracts forms under delegated management

In the case of fully privatized utilities, private-sector corporations own and operate the water supply infrastructure. Relatively few examples of fully privatized water utilities exist. Where they do exist, they have usually been created through the sale of a public utility to the private sector.

Table 6 below presents the public-private partnership type adopted by sample countries in their water privatization processes. The most common type of partnership is delegated management as many countries refrain, at least at this stage, from full privatization. Concessions and leases seem to be the most common contract form under delegated management. Under these contracts, the assets remain owned by the government.

Table 6 Partnership and contract types in sample countries

Each of the above mentioned partnership types, carry its own advantages and disadvantages. Advantages mainly include:

- Availability of finance

- Better efficiency and effectiveness

- New technologies.

As for the main disadvantages, they include potential monopoly, increased prices to users, and high costs relative to perceived risks (Bakker, 2003). A disadvantage that is of more concern to fully privatized utilities is that such a model is difficult to reverse.

As observed in Table 6, regulation goes hand in hand with the different partnerships and contract types, however, the nature of the regulatory agency differs as each country sees fit. Indeed, advantages are doubtful in the absence of regulation. As such, efficiency and innovation only occur if regulation is effective. Published literature emphasizes the role of regulation in privatization processes as a tool to ensure transparency and accountability of private companies and utilities to the government and more importantly to the (Castro, 2007; Bakker, 2001). Regulation needs to include all aspects of privatization, from network expansion to water pricing, and management of theft and no fee-payment to be effective.

It is important to mention that the water privatization projects in different countries differ significantly in size. The number of contracts awarded is not directly related to the total investment in privatization projects in the country. For example, the three countries with the highest number of projects undertaken by the private sector, ‘China, Mexico and Brazil, have awarded only small contracts, and make up 7 percent only of the investment in developing countries. By contrast Argentina, the Philippines, and Malaysia have awarded 16 private projects, which comprise 69 percent of all private investment in the water sector’ (Castro, 2007).

Impact of privatization

From 1990 onwards, private participation in the water sector in developing countries started increasing and a growing number of governments are turning to the private sector to build, recover, expand and/or operate their water and sanitation networks. In the years up to 1997, more than 90 projects, in thirty-five countries, about water resource management have been undertaken by the private sector. Hence, it is observed that the private capital investment for water projects in developing countries is increasing together with the increase in the number of projects (Gray, 2001).

Case studies published in academic literature show that private sector participation in the water sector is likely to result in improved managerial practices and higher operating efficiency (Comair, 2005). On the whole, available evidence suggests that private involvement can improve, significantly, service provision to the poor and save budgetary resources for other, perhaps pro-poor, projects. In many cases, poor households show high motivation to pay for improved services with contingent valuation studies (Tynan, 2000). Most common developments achieved by private sector participation in water

sector can be categorized into:

- Improvement in water service quality;

- Improvement in water production efficiency;

- Diminished water losses;

- Strengthening of management of the water sector, and

- Enhancement of customer care.

To achieve these improvements, the private sector has invested in the expansion of coverage and in regular maintenance and has enhanced billing and revenue collection activities. This, indeed, required a significant rise in the cost of water, as observed in England, France, Mexico, Kenya, Tanzania etc. (Nyangeri Nyanchaga, 2003; Azpiazu et al., 2003; Mashauri, 2003; Torregrosa, 2003; Bakker, 2003). The demand reaction to these privatization improvements can be summarized by overall satisfaction with the services, but accompanied with complaints about the high water cost. Interestingly, privatization was accompanied with variable average per capita consumption rates. It is reported that, after water privatization in Kenya for instance, the average per capita water consumption increased in parallel to the water cost increase (Nyangeri Nyanchaga, 2003). This can be attributed to the improvement of water quality and service under privatization, which rendered the current increased price as still cost-effective.

Private participation can also improve competency in the water sector in several ways. Introduction of competition brings efficiency gains; the most important of which comes from changing the incentive structure, inducing innovation and influencing investment decisions. Privatization may also affect water prices where more than one scenario exists. First, if prices were initially fixed at below-cost levels, then prices after privatization would need to increase as prices should cover production cost. Second, efficiency savings achieved under privatization will generally lead to a drop in prices with some gains passed on to consumers. This is due to the decreased efficiency losses, proper maintenance and consequent saving of water which have been otherwise lost and need to be replaced adding up to the cost. Third, the total cost of private financing may bring about an increase in prices. Hence, prices after privatization will reflect full costs and the consumer will be charged instead of the taxpayer.

Positive Experiences from selected countries

England and Wales is a typical example of private participation in infrastructure. Privatization in the water sector started in 1989 when the regional water authorities, owned by the central government, were privatized by flotation on the stock exchange (Bakker, 2001; Bakker, 2003; Dore et al., 2004). The reasons behind this included the efficiency of the private sector and the financial ability of private companies to finance the large investments needed to repair the water systems in addition to increased competition (Dore et al., 2004; Bakker, 2003). These private companies were responsible to provide the entire cycle of services from extraction of raw water, delivery of processed water and collection, treatment and discharge of wastewater (Bakker, 2003).

This privatization ‘entailed a change in the ownership, financing and regulation of the water industry’ (Bakker, 2003). To this end, England developed extensive regulatory frameworks for the water sector to protect consumers and public health: “companies were forbidden from disconnecting domestic consumers (even for non-payment of bills), and were required to create special, low tariffs for vulnerable consumers. They were also required to submit strategic financial plans as well as resource development and water supply management plans to an economic regulator and an environmental regulator for review” (Bakker, 2003).

As such, an environmental regulator, an economic regulator and a drinking water quality regulator were created where the economic regulator relied on price caps and yardsticks to improve competition (Dore et al., 2004; Bakker, 2003; Littlechild, 1988). However, it is believed that such regulatory efforts have heavy requirements with regards to information (Van den Berg, 1997). At that time, the water industry in England and Wales was best characterized as “publicly regulated private monopolies operating on modified market principles” (Hay, 1996; Bakker, 2003). Nonetheless, the water industry in England has been re-regulated (Bakker, 2003). Some companies have entered into delegated management contracts, and many have replaced equity financing with bond financing.

Today, in England and Wales, nine of the ten water companies that were privatized by public flotation in 1989 continue to operate as private companies (Bakker, 2003). Nevertheless, in 2001, the tenth company was restructured into a not-for-profit water utility as a potential to lower the cost of capital and reduce customer bills after prices increased beyond inflation rates since 1988. Glas Cymru, a utility company, now runs as a private company owned by its members (Bakker, 2003). In general, it is reported that privatization in England and Wales has led to water quality and environmental improvements but at higher water prices (Dore et al., 2004).

In Australia, Sydney Water, a State Owned Company operated till 1995, and thereafter as a Statutory Authority incorporated in 1995, was responsible for capturing, storing, treating and distributing water in Sydney. Faced with major capital expenditure to improve and expand water treatment capacity, and having established private enthusiasm to pay for services, Sydney Water decided to subcontract to private companies for privately built, owned and operated (BOO) systems of water treatment. Prices were regulated by a Government Pricing Tribunal, now an Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal. Following some abnormal climatic conditions that led to the deterioration of water quality, major concerns have been raised about quality of services unforeseen in the contract, putting the contractual relationship under pressure. It remains to be seen what impact such events might have on risk sharing, contractual transparency and regulation (Chapman & Cuthbertson, 1999).

Another considerable efficient case is that of Bolivia. In Santa Cruz, the largest city in Bolivia, home to one million people, the world’s largest co-operative, known as SAGUAPAC operates. It has proved to be highly competent and successful. The unaccounted-for-water levels are relatively low, all connections are metered, the number of employees per 1000 water connections is quite low and there is a 96 percent bill collectionefficiency rate. Its positive impact can be attributed to two key advantages: its co-operative structure shields management from excessive political interference: it can put into operation investment projects much faster and more competently than other companies since it is not bound by legal delays; and it can finance an external loan more easily. Nevertheless, a successful co-operative is an exception rather than the rule, as the experience with the co-operative model in different sectors worldwide is rather disappointing (Crespo et al., 2003).

In parallel, a study done by Megginston and Netter (2001) that reviewed 61 cases of water privatization concluded that privately managed firms tend to be more productive and profitable than public firms in both developed and developing countries (Megginston & Netter, 2001).

In Senegal, after signature of contract with Saur in 1996, water production increased by 20% between 1997 and 2002, the number of customers increased by 50% between 1996 and 2003, and the network commercial rate improved from 68% in 1996 to 80% in 2006 (Carcas, 2004; UNESC 2005). Similarly, a management contract between Suez and Johannesburg Water in 2001 for the suburb of Soweto in South Africa reported dramatic decreases in leakages and unaccounted-for-water losses (Blanc & Ghesquières, 2006).

In the city of Indianapolis, where it has created a successful public-private partnership with Veolia Water, the city is gaining economic and environmental benefits where the partnership saves local governments an $85 million during the 20-year contract. In addition, it has also greatly improved the problem-ridden billing system, and caused the drop of customer complaints down from 500 in 2001 to an annual average of 30 (DLC2003).

Public – private partnership has been practiced in the water sector for two decades now, and it has shown that the private sector can help mobilize financing, implement investment programs, and improve performance of service delivery. Therefore, PPP is worth considering as one way of bringing in efficient management skills and fresh funds and relieving government of fiscal and administrative burdens. However, it is unrealistic to expect that any short term privatization can overcome the inherited institutional and operational in-efficiencies of the public sector. Privatization has encountered several problems, such as unfavourable macroeconomic conditions, political involvement, inadequate incentives, and weak regulatory frameworks (Nyangeri Nyanchaga, 2003). It is worth re-iterating that the failure to establish clear regulatory frameworks, threaten thesustainability of any private sector involvement.

Drawbacks of Privatization

Published literature also provides case studies where privatization of water was not the solution, but further exacerbated the water problem (Bortolotti & Perotti, 2007). Reasons reported behind privatization failure include the following:

Unacceptability to consumers of private sector participation because they were not involved in the privatization process (Nyangeri Nyanchaga, 2003);

Opposition of consumers to the high water costs leading to their withholding payment, as well as increased dependence on other alternative water sources (rivers) (Nyangeri Nyanchaga, 2003; Birdsall & Nellis, 2002);

Private companies’ unacceptable practice of disconnecting users that are not paying,which can lead to widespread undesirable health conditions (Torregrosa, 2003; Dore et al., 2004).

This emphasizes the role of regulation and associated measures as the cornerstone of sustainable public-private participation in the water sector. Whilst there exists no universally applicable regulatory model, effective regulation relies on effective regulatory institutions, strong public administration, adequate incentives and regulatory instruments and, indeed, the enforcement of these regulations. In fact, there have also been cases of privatization withdrawal from sectors and countries (Auriol & Blanc, 2007; Harris 2003).

Negative Experiences from selected countries

The World Economic Forum reports that public criticism of private sector participation in water infrastructure rehabilitation and expansion is common; the most frequent charge is that networks are not extended to the poorest (World Economic Forum 2004). Similarly, surveys from Sub- Saharan Africa and South Asia show strong popular opposition to privatization policies (Kikeri & Kolo, 2005). In fact, Africa, privatization reforms have been qualified as "re-colonization" due to the participation of foreign firms in many cases (Auriol & Blanc, 2007).

Al-Alawi (1998) in his study of privatization in gulf countries, he concluded that the sudden rush towards privatization has resulted in unfortunate obstacles mainly attributed to:

- ‘No thorough planning and inadequate preparation by governments in defining their long term objectives of privatization.

- International consultants and developers imposing privatization structures that worked elsewhere in the world, but are not suitable for the Gulf States.

- High levels of subsidies for water and electricity.

- Absence of real competition resulting in very high unit costs proposed by developers of independent electricity and water projects.

- Scarcity of water in this area of the world, and the requirements of desalination processes, dictate the need for combined planning and operation of water and electricity utilities in order to maximize efficiencyand reduce overheads.

- Unique local problems such as legislation, risks, lack of local knowledge’ etc. In Kuwait, for example, the same water problem persisted under privatization, which was expected to message them.

These include the policy for seawater desalination itself,combining desalination units with steam turbines, and lack of timely response to match increases in water demand with increased desalination capacity, as well as the lack of measures and public incentives for water conservation, unrealistically low pricing of water and power, the lack of awareness of the cost of water in homes and public buildings like mosques, and schools, and the high cost of desalinated water production (Darwish & Al Najem, 2005).

Moreover solid research done in three studies that reviewed 204 privatizations in 41 countries showed that one-fifth to one-third of privatized firms have registered very slight to no improvement, and even worsening situations occasionally (Megginson & Netter, 2001). In Malaysia, for instance, after the government awarded a 28-year concession to a private consortium, to carry out improving, rehabilitating, and extending the country’s sewer system, progress has been considered quite slow because of major public and commercial repercussion from tariff collection and tariff increases (Estache & Rossi,1999).

A rather interesting yet alarming finding is what Harris (2003) reported on private firms who retreated from utility services, notably in water and electricity, due to their disappointment by the profits they secured indeveloping countries and unpopularity of their actions (Harris, 2003). Examples of these companies include Veolia in Guinea, Saur in Mali, Hydro- Québec and Elyo in Senegal, Thames water in East Djakarta and Biwater in Tanzania (Auriol & Blanc, 2007). For example, water privatization in East Jakarta began in February 1998 with the award of a 25-year water concession to a subsidiary of the British firm Thames Water International for the management, operation, and maintenance of the city’s water supply system including the provision of capital investment, billing, and collection (Andrews &Yniguez, 2004).

The 1997 East Asian financial crisis carried major financial problems where the water rate increased by 15% in February 1998, 35% in April 2001, 40% in April 2003 and 30% in January 2004 (Hall et al, 2005). Consequently, the contracts were renegotiated in 2001 and the Water Supply Regulatory Body was established as an "autonomous" regulator in charge of supervising the concessions (Hall et al, 2005). In 2003, it was reported that Seven years into the privatization investments and efficiency has not been majorly improved in East Jakarta as consumers still complain of poor service and frequent water disruptions. Consumer groups sued the concessionaires for providing poor services;however, in early 2004 a regular increase of tariffs every six months between January 2004 and 2007 was agreed. In a similar case, the government in Tanzania was forced into privatizing its water system by donors, including the World Bank and European Investment Bank, as a precondition to receive aid. Starting 2003, City Water, a Biwater joint venture, was contracted through a leasing scheme to provide water and wastewater services in the city of Dar-es-Salaam (USLaw Blog Directory website) for ten years.

However, in 2005, just two years after the contract signature, the Tanzanian government cancelled the concession (PSI website) highlighting that the City Water neglected continuously the installation of pipes to households, have not made the required with continuous water quality decline (Food and World Watch website). To this end, Biwater filed a case against the Dar-es-Salam Authority but the international arbitration panel ruled against the company where it found that City Water failed to fulfilcontractual clauses and that Tanzania's decision to cancel the contract in 2005 was justified. The panel also awarded Dar-es-Salam Authority US$8 billion in damages enough to provide improved water to more 53,000 people in Dar-es-Salaam (PSI website; Food and World Watch website).

In a similar case, in Argentina, privatization was initiated in 1991 through a process of restructuring of most of the state controlled public service companies, which also included the national monopolies in water. This privatization act aimed to create competition that would benefit consumers through reduced utilities fees (Ivanier, 2007).To accompany the privatization process, the government created a regulatory entity to control the operations. However, instead of de-bundling the water service into production, transportation and distribution, the government maintained the integration of this service when offered for bidding. In April 1993, the concession was signed with Aguas Argentinas S.A. led by a French firm. The case of privatization in Argentina is controversial where it has ended by a revoke of the concession and the re-statization of the water services and where an arbitration case is still pending under the International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (Ivanier, 2007). This experience carried both advantages and disadvantages to Argentina. With respect to the advantages, within the first two years of operations, production capacity expanded by 27 percent (Azpiazu et al., 2003), and in the 14 year concession services of potable water expanded to include 1,700,000 (Ivanier, 2007) with a drop in the response time for repairs to just two days (Azpiazu et al., 2003). Moreover, it was shown that child mortality dropped by 5 to 7 percent more in areas included under the privatization scheme compared to the others particularly in the poorest areas (24%) (Galiani et al., 2002).

However, the private company acted as a monopoly where it reaped unusual benefits of a total of above 5 billion dollars (Ivanier, 2007). Moreover, and due to no re-investment of profits, the company became indebted for about $300 million dollars. Moreover, the population was prone to arbitrary pricing under this monopoly where tariffs were increased by 88.6% (Azpiazu, 2002). In result, the Argentinean government announced in 2006 the rescission of the contract and the re-statization of the service. The reasons highlighted by the government included the company’s incompliance with commitments where that the company fell short of its original commitments over the first five year plans by 58% and over the second five year period by 90% (ETOSS 2003; Solanes, 2006).

The case in Argentina represented an important case of the reversal of privatization; however it was not the only case. In a similar case, Uruguay sought private sector participation in water supply and sanitation to improve the efficiency and the quality of the water service. To this end, it signed two concessions for water service operation in two cities and created a utility regulatory agency to overview the water sector. However, allegations of overcharging and poor service quality arose associated with campaigns against the companies. In result, the concession of URAGUA was withdrawn in 2004 and the Uruguayan Parliament amended the constitution to prohibit any form of private sector participation in the water sector.

In Bolivia, the government signed a 40-year concession with Aguas del Tunari of International Water Limited, which aimed to provide water and sanitation services to the residents of Cochabamba (Finnegan, 2002; Nash, 2002; CNN 2000). However, after one week of taking control of the Cochabamba water supply system, the company imposed a large rate increase where bills reached 28% of monthly incomes in the area of service. This led to a big wave of demonstrations in 2000 in Bolivia and Washington D.C. leading to a state of emergency in Cochabamba. This issue was highlighted by its critics as an example of corporate greed and a reason to resist globalization. The case ended by 2006 where a settlement was reached between the Government of Bolivia and the company who agreed to terminate the concession due to civil unrest in Cochabamba while dropping any financial claims against one another and not discussing performance or contract (Bechtel website).

To this end, a UNDP report in 2006 assessing water privatization in different countries concluded that the overall results were not encouraging; stating that “From Argentina to Bolivia, and from the Philippines to the United States, the conviction that the private sector offers a magic bullet for unleashing equity and efficiency needed to accelerate progress towards water for all has proven to be misplaced. While these past failures of water concessions do not provide evidence that the private sector has no role to play, they do point for the need of greater caution, regulation and a commitment to equity in public-private partnerships” (UNDP 2006; 10).

This in fact the most informative conclusion of the above listed positive and negative experiences that showed that privatization is a double sided sword whose positive contribution is conditioned to proper planning, regulation and government active overview.

Further Reading

After this overview of the concepts of water scarcity, water sustainability, and water governance in general terms, it is important to investigate their understanding and implications in the area of study i.e. West Asia region in general and UAE in particular. In addition, after the general introduction of privatization and assessment of its impacts on water resources, it is now imperative to put it into the context of the area under study.

Resources

This article was written by Dr, Mohammed Yousef Al-Madfaei. The issues covered in the article are covered in more detail, in his PHD Thesis: THE IMPACT OF PRIVATISATION ON THE SUSTAINABILITY OF WATER RESOURCES IN THE UNITED ARAB EMIRATES, of 2009.

The thesis looks at water resources and supply in United Arab Emirates in terms of water scarcity, sustainability and governance. The arid climate and low annual rainfall of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) present several difficulties for sustainability of the nation’s water supply. With a national annual renewable water resource capacity of only 64 m3 per capita, UAE exerts great pressures on its limited renewable water resources; utilizing groundwater, surface water, treated wastewater and desalinated water to meet increasing water demands. This research investigates potential contributions by the privatization of water production to sustainability ofwater supply in the UAE. The main objective was examination of perceptions of UAE stakeholders concerning privatization as a water governance model and its contribution to water sustainability. The approach adopted in pursuit of these objectives was based on the collection of qualitative and quantitative data from water officials and consumers in three representative Emirates of UAE; Abu Dhabi with a full privatized water management system, Dubai with a semi-privatized system and Fujairah with a full public system. The analysis revealed an acceptance of UAE residents of public-private partnerships under the delegated authority watergovernance model. It also showed that residents think privatization could potentially ensure sustainability due to the associated benefits of effectiveness and efficiency achieved through continuous maintenance and demand management through proper pricing. This research provides a robust reference for future planning in the water sector of UAE, hinting at the importance of considering public-private partnerships at the federal level as an appropriate model for water sustainability.